- Thu 30 November 2017

- open-access

I have lately been telling people that my research tries to make Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) "less wrong." It's a nice line, pithy and fundamentally true. There are enough challenges and money in LCA to support the careers of many research scientists. As LCA is still relatively young, there are also nice problems, ones requiring both creativity and techniques from a variety of disciplines. Most days, I get to both enjoy my job and feel like I am making an actual contribution to the community and (hopefully) to better decision-making.

A totally normal thing to do on a big birthday: Dress up as Snow White and go on a family bike ride with 5000 of your closest friends and neighbors.

I turned forty in August, and had some time to think about what I have accomplished, and how best to use my interests and talents in the future. My wife claims I am having a "mini mid-life crisis." I'm not sure about that - forty is a significant milestone, and it's natural on such dates to think about life's goals and possibilities. In any case, I am glad I had a chance to reflect a bit, as it has helped clarify my feelings over the current state of practice in LCA. During my PhD and postdoc work, I was focused on methodology development, and never really did any actual LCA studies - it was only after I started work at the Paul Scherrer Institut in 2014 that I had to stand in a room and explain to the interested parties what we did and what conclusions we reached. I recognized then that there were limitations in our work; I can now better articulate what I feel these limitations are.

We don't know how wrong we are

The scope of LCA is rather modest: We try to model the entire modern economy and its interaction with the natural environment. Despite the magnitude of this challenge, and the potential importance of LCA in an era of global environmental challenges, it seems to me that "validation" a somehow dirty word for us - not something which is brought up in polite conversation. One difficulty is that it can be difficult to find truly independent sources of validation data results (though there have been some attempts). But the unknown unknown of how badly current LCA databases get their answers wrong due to incomplete coverage of the industrial and natural world is a critical problem. We must have validation both at the unit process level, and of the database as a whole!

Luckily, this problem is not insolvable. We can new and independent data sources to validate our large and small scale models. For example, in just the latest two issues of Environmental Science & Technology, I found the following:

- Ammonia Emissions May Be Substantially Underestimated in China

- Additive Models Reveal Sources of Metals and Organic Pollutants in Norwegian Marine Sediments

- Airborne Methane Emission Measurements for Selected Oil and Gas Facilities Across California

- Comparisons of Airborne Measurements and Inventory Estimates of Methane Emissions in the Alberta Upstream Oil and Gas Sector

An online dashboard showing our collective progress towards a set of validation indicators would be a great first step.

Lunch isn't free, but someone has already paid for it

The value of most of what we publish is wasted, because it is too hard to contribute useful information back to the broader community. Background databases are focused on larger institutions that generate many datasets at once. Software used for LCA studies almost never supports easy submission of data to background databases or online web marketplaces. While there are commercial products that try to make data sharing within their software easy, they are built as data silos that severely restrict the ability to export data in such a way that it can actually be used by others.

Data might not be free [1], but it is available in the supporting information of most published studies. In the short term, we need software that can make it easy to extract this data; in the long-term, we need a tools and community standards that make data submission the norm, and easy to do. People worry about providing incentives for sharing data, though there is a movement towards requiring open data in at least some industrial ecology journals. In the end, the blunt truth is that scientific articles must be falsifiable and reproducible or they aren't science. For now, although manually extracting data from many studies won't be fun, we know it can be done successfully.

Uncertainty exists, and can even be useful

People laugh a little nervously when I tell them that LCA results are always wrong. It's an uncomfortable truth: models are always wrong, and LCA is turtles (models) all the way down. LCA results can be useful, though, and useful LCA results need uncertainty analysis at each step of the calculation chain. We need to do a better job providing documentation and tools for estimating uncertainty in inventory dataset development; we also need to convince impact assessment developers that characterization factors without uncertainty are unusable. Similarly, it should be easier in tools to assess uncertainty in system models, like Ocelot, to vary and assess the impact of individual modeling choices [2].

In many cases, we can mitigate the introduced errors of fitting uncertainty distributions to multimodal data and subsequently drawing independent Monte Carlo samples by drawing directly from population data or from pre-generated samples. Such "presamples" would include correlations among inputs (e.g. temporal patterns of inputs to electricity market mixes), and can also include mass or energetic balances within or across product systems (e.g. fuel consumption and CO2 emissions), multiple outputs from non-linear inventory models, and even correlation among characterization factors in both site-generic or regionalized impact assessment. Pascal Lesage and I have already started working on implementing these ideas.

Some LCA studies can have millions of uncertain parameters. This doesn't make uncertainty assessment difficult, but it does make sensitivity analysis expensive. Our uncertainty toolkit must be flexible enough to allow for various computational frameworks, like regionalized assessment or nonlinear impact assessment models, as well as many different uncertainty distributions and drawing directly from "presamples". The only reasonable approach I can see is that addresses all these needs is to do aggressive sensitivity screening to reduce the problem space by discarding low impact parameters before starting a calculation, and then global sensitivity assessment of the reduced parameter set. Both operations are embarrassingly parallel and should be dispatched to the cloud, and screening calculations for databases can be cached and provided as a community resource. Luckily, the field of uncertainty quantification is vibrant, and offers us many alternatives for both steps.

The importance of open data and open source software

Open societies have public debates over important decisions, and these debates are informed by stakeholders who represent different points of view. Anytime LCA is used in democratic decision-making, either in government or in direct communication with citizens (e.g. ecolabels), both the underlying data and the calculation methodology must be completely open to inspection and alteration. Closed data and models prevent building trust, hinder informed debate, and obstruct consensus among different elements of civil society. Too often, conflicting LCA studies have led to people reverting to ideologies and discarding the ability of LCA to contribute neutral scientific knowledge. Open data and models allow groups on all sides to engage with and help improve our results. There are also numerous other benefits of open source software.

Inspiration from the amazing Open Energy modeling community

I attended the seventh Open Energy Modelling Workshop in München this fall, and was humbled by their passion and accomplishments. Although closed source energy models are still widely used, there is a thriving ecosystem of open source models and data. The community also holds in-person workshops every six months; although few who participate have specific travel funding, as a group they recognize the increased value of working together as a community. LCA folk have the passion and expertise to do something similar, if we decided to.

BONSAI, or something like it

It took me a while, but I am now a BONSAI convert, and I agree completely with Bo Weidema - I am also embarrassed by the comparison between LCA and other subject domains. The vision of an open RDF-like store with a massive amount of data that can be queried, assessed, and used to support all of industrial ecology would be enormously useful. The separation between raw data and the models that build inventories is also correct and necessary. Ocelot already allows us to investigate the relative importance of modeling choices and assumptions when aggregating unallocated inventories into a database instance; we need something similar for the construction of individual inventory datasets.

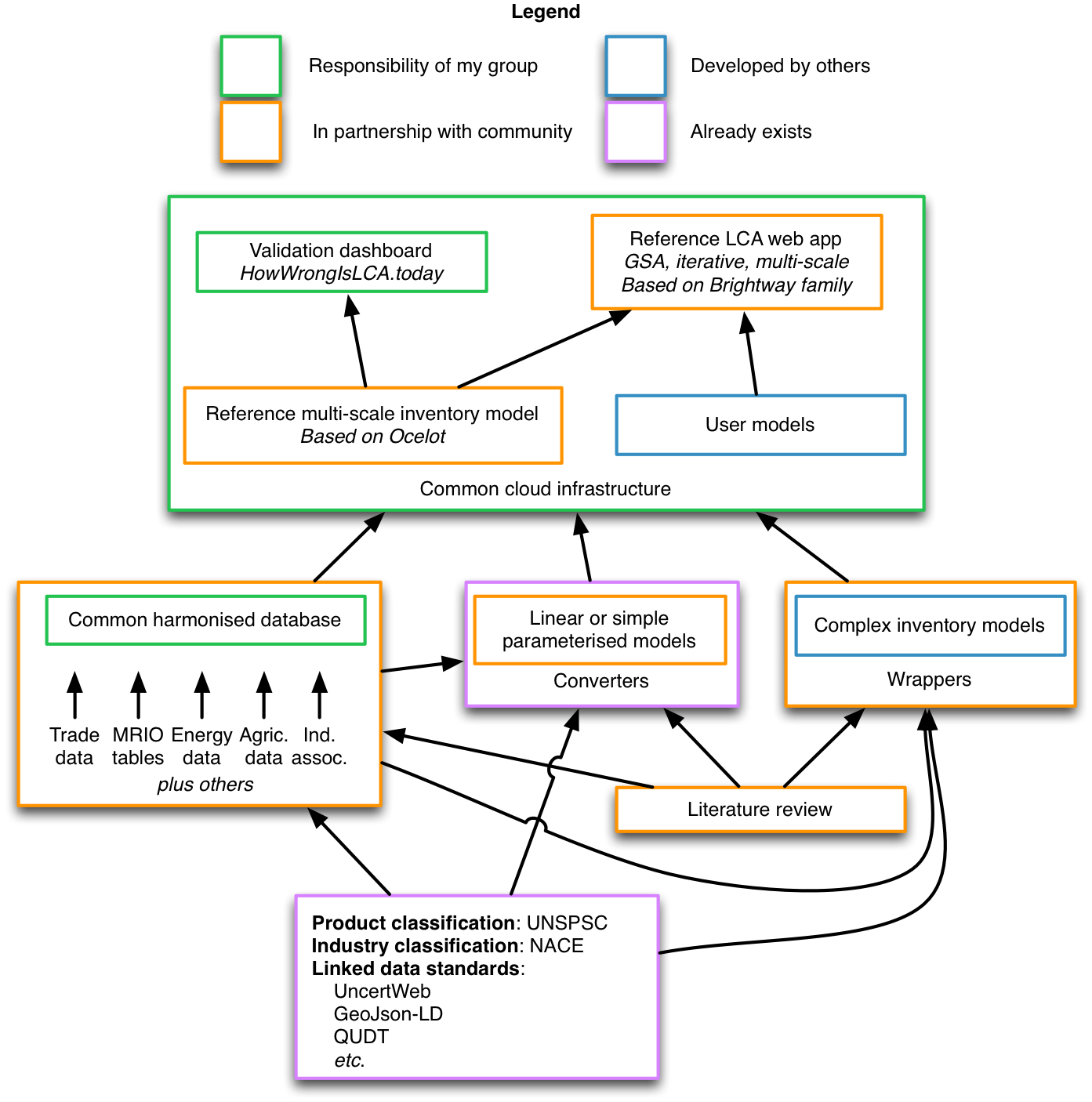

One plan for the future

The foundation of any new approach should be a set of coherent ontologies. There are nice linked data schemas for units, time, space, and other fundamentals; we also have internationally accepted product and industry codes. Any transformations from other systems should be transparent and clearly documented. I am sure that there were good reasons to invent activity and product names back in the day, but such idiosyncrasies only inhibit us now.

The common harmonised database should include everything we can. There is a lot of free, high-quality data out there - seriously, there is a lot! Instead of choosing a single global multi-regional input output table, we should have all of them available as supply and use tables. The use of schemas, as in DBpedia, will give structure and predictability to this data. Whether we use a RDF graph database or something simpler is an open question [3], and should be based not just on technical measures like query speed, but also on the ability to engage the community. The harmonised database has to be easy to consume, validate, and submit to.

At the same time, we don't want to ignore existing inventory datasets or models. Much of the value of existing LCA studies is in their detailed understanding of specific technologies. Existing datasets need to be converted to our base ontology, and our format converters need to be fully functional and lovingly maintained. More complex models will need to be wrapped to allow for their use as linearized inventory datasets at given production levels.

The aim of this aggregation is to produce sets of data that can be fed into a system model to produce an inventory database. There should be one reference database, which will serve not as the "right answer", but rather as an example of how such system models can be built and tested. In addition to normalizing many different data sources, aggregating many sources into a harmonised database also allows for better performance of our system models.

The reference system model also needs to be multi-scale, aggregating products and sectors where their environmental or social performance is similar, while still allowing for disaggregation when desired. Incidentally, data licensing will work the same way, just as it does on Google Earth. At a high level, aggregated or generic data is enough for initial conclusions. As you zoom in into a particular sector, we need to show which data sources are being used, and the restrictions on those licenses. Some datasets, for example, are free for research but not for commercial use.

System models can choose which data sources to consume, and how to weight the quality of these input data streams based on uncertainty information or other metrics. We now have a solid foundation for such models. There is still great potential for research here, though, and assuming our harmonised database is large enough, machine learning techniques could be applied for assessing data quality or other useful tasks, like disaggregation.

The online validation dashboard is a critical element in the overall system. This should chart our progress over time towards our validation milestones, which will be themselves an active area for research. We will also track the overall uncertainty of the system. Advancements in the harmonised database and reference system model should be prioritized based on weaknesses identified in the validation procedure.

In the beginning, the focus for the reference application should be on improving existing inventory builders by using iterative underspecification and global sensitivity analysis.

Research into practice

Software might be eating the world, but it isn't eating the LCA world quickly enough. Research projects or academic publications without tools that can actually be used by the practitioner community won't have an impact outside of one's CV. Research as part of this initiative must therefore be accompanied by implementations and tools that are freely accessible, and easy to use and integrate into data workflows. Designing reusable interfaces is not easy; one possibility is to get community consensus on example reference interfaces. This will be an active area of practical research, and will require several iterations.

The next steps

Personally, I am beginning to recognize that my role is shifting. Instead of working in detail on projects, I need to be more of a manager and organizer. I still enjoy programming, and being able to solve challenges through the use of computer programs, but I also feel an obligation to use the skills I have developed and my natural talents to work for the broader community, not just for myself and the issues that interest me in the moment. That means acquiring funds and organizing groups - particularly with people outside of the usual LCA suspects. I am currently exploring a number of options that would allow me to work more intensively with other computer scientists.

This idea can't be realized by one person or one group. There is too much to do, none of us have all the requisite subject expertise, and together we make wiser decisions. Somewhat surprisingly, at least for me, is the fact that in Europe, there is currently very good support for open data and resources for running open models, so computational resources should not be a limitation. In the chart above I have identified areas in green where I have a reasonable ability to make helpful contributions - these will also be areas where I will be directing my efforts in the near future. But this plan is not about me, and it can't work through centralization. Individual initiatives are necessary but not sufficient without community support and ultimately consensus. We need to test many different ideas and approaches, and to involve people from new disciplines.

Conclusion

We are in a bit of a mess. Although LCA continues to grow through programs like the PEF, there are fundamental weaknesses that desperately need to be addressed. The most important is our lack of validation; we don't know how wrong our results are. Our understanding of data quality and uncertainty also needs to be radically improved. Although there are a number of commercial and free databases available, it is too difficult to make data available and useful to others, and existing database development could be better prioritized based on validation results. I present one possibility for a future community-driven model, where a common harmonised database would allow for institutions to develop and apply their own system models and inventory databases. Such a data and computation infrastructure could help alleviate the problems I identified, and would be useful not just for LCA but for industrial ecology in general. I also think that the resource investment in building such a system would be paid back many times over in the improvements to the quality of our results.

At the LCM conference in Luxembourg this fall, I saw a presentation from Christopher Oberschelp of ETH Zürich which tried to develop detailed inventory datasets for over a thousand power plants in China using a combination of new data sources and optimization. Imagine a world in which he could refer to an automatically generated report showing that uncertainty and lack of data on these generators were degrading the quality of all LCA results, and that his contribution improved scores against a variety of validation indicators drawn from official statistics and remote sensing. Of course, at the end he wouldn't need to mention that this new data was already publicly available and integrated into the harmonised database - it would just be expected. These building blocks are all available today; together, we can construct something great.

Acknowledgments

As should be clear from the numerous links through this document, I have been inspired by a number of smart, creative and challenging people, either in person or through their published work. Thanks also to Bo Weidema, Michele de Rosa, Brian Cox, my dad, Tomas Navarrete, and Stefan Pauliuk for comments on a draft version of this document. Credit therefore belongs to many; any mistakes are, of course, my own damn fault :)

Footnotes

| [1] | While it is a tautology that something which needs resources to be produced is not free, one long-standing function of government and other societal actors is to make investments that produce much more societal value than their costs; this is such an obvious point that it bears no further discussion. |

| [2] | Sorry, that one is my bad. |

| [3] | RDF graph databases have achieved moderate success in the market, and should be on option for the harmonised database storage system. I think it would also be worthwhile investigating two alternatives: hashed documents stored on a decentralized service like IPFS, and schema-compliant immutable SQLite databases stored on a CDN. |