- Mon 14 January 2013

- uncertainty

- #notable

Uncertainty in ecoinvent

The ecoinvent database (version 2.2) characterizes inventory data uses the following uncertainty distributions:

Here are the number of biosphere and technosphere exchanges:

| Distribution | Technosphere | Biosphere |

|---|---|---|

| Undefined [1] | 1629 | 37036 |

| Triangular | 8 | 0 |

| Normal | 27 | 16 |

| Lognormal | 37314 | 54032 |

| Distribution | Technosphere | Biosphere |

|---|---|---|

| Undefined [1] | 35388 | 188562 |

| Triangular | 12 | 0 |

| Normal | 1 | 60 |

| Lognormal | 120456 | 175726 |

| [1] | (1, 2) Includes exchanges labelled with the lognormal distribution, but with a standard deviation of zero, giving them no uncertainty. |

And here is how I generated these statistics using Brightway2:

from bw2data.backends.peewee.schema import *

from collections import Counter

from stats_arrays import *

def statistics_for_database(database_name):

labeller = lambda x: 'technosphere' if x != 'biosphere' else 'biosphere'

return Counter(

(

# Label technosphere or biosphere

labeller(exc.type),

# Get name of uncertainty distribution

uncertainty_choices[exc.data.get('uncertainty type', 0)].description

) for exc in ExchangeDataset.select().where(ExchangeDataset.output_database == database_name)

).most_common()

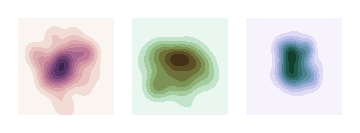

It's clear that ecoinvent has a (almost unhealthy) love for the lognormal distribution. Why is the lognormal distribution so popular? Let's briefly review the normal and lognormal distributions.

A little bit of theory

First, we should begin by saying that normal means normal in the mathematical sense, i.e. orthogonal, and can also be called the Gaussian distribution. However, normal turns out to be quite a name, as this distribution, with it simple mathematical form and properties underlines much of frequentist statistics. The normal distribution is also the core of the central limit theorem. The normal distribution is defined by μ, the average, and σ, the standard deviation.

If a dataset is lognormally distributed, then the natural logarithm of that dataset is normally distributed. Naturally, the opposite works as well: if a dataset is normally distributed, then the exponential of that dataset if lognormally distributed. The lognormal distribution is just a small mathematical variation on the normal distribution, therefore, and the lognormal distribution is still defined by μ, the average, and σ, the standard deviation of the underlying normal distribution.

The geometric mean of a lognormally-distributed dataset, is defined as the exponential of the mean of the underlying dataset:

However, the geometric mean is not the mean of the dataset values, but rather the median (this might be where things start to get confusing - it sure was for me!). The mean of the un-transformed data is instead:

Now you should understand why a static LCA calculation, which uses the median values for all lognormally distributed random variables, will give a smaller answer than the average Monte Carlo result.

One last bit of theory: if you add two normally-distributed datasets, you get a normally-distributed dataset. If you multiply two lognormally-distributed datasets, you get a lognormally-distributed dataset. Here are the formulas for the multiplication of two independent lognormally-distributed datasets, X and Y:

Put another way, when you multiply two lognormally-distributed datasets, the resulting standard deviation follows the normal formulae for propagation of uncertainty (bearing in mind that σ is the standard deviation of the log-transformed dataset), while the new median value can be arrived at two ways: first, by multiplying the median values of the two original datasets, or by adding the means of the log-transformed dataset (and then applying the exponential function to get the median value again).

Why choose the lognormal distribution?

Now we are ready to explain the 19th century English novel troubled romance between ecoinvent and the lognormal distribution. First, because the lognormal distribution is asymmetric, it is always positive, whereas the normal distribution is symmetric and crosses the zero line. This is a very simple but important reason to choose the lognormal distribution over the normal distribution [2].

Second, there is some evidence that the lognormal distribution occurs frequently in natural phenomena [3].

Third, the simple mathematical properties of the lognormal distribution make it is easier to work with (e.g. multiply two independent distributions) than other asymmetric distributions.

Finally, the simple mathematical properties of the lognormal distribution allow the use of the pedigree matrix.

| [2] | There are actually two ways that the lognormal distribution can be negative. First, there is a three-parameter variant of the lognormal with a shift parameter which could shift the distribution to the left, i.e. into negative values. Secondly, most values in the technosphere matrix are negative - exchanges which consume inputs are negative - so even though we define our exchanges with positive numbers, we then multiply then by negative one when using them in LCA calculations. However, the general conclusion in this second case remains - values from the two-parameter lognormal are either strictly negative or strictly positive. |

The pedigree matrix

The pedigree matrix is a complex beast, and you can read about the details and specifics of the uncertainty factors in the technical report [4]. The summary is that the pedigree matrix is a way of adding uncertainty to existing uncertainty distributions by broadening them without changing their median values. In other words, applying the pedigree matrix increases σ, but doesn't change μ. This works because each uncertainty factor in the pedigree matrix represents the multiplication of a lognormally distributed dataset by the pedigree uncertainty factor, which is another lognormally with a μ of zero.

Although the pedigree matrix is currently defined only for the lognormal distribution, the basic principle of increasing uncertainty by broadening the distribution while not changing the median (or mean, depending on the distribution) has been applied to other distributions in ecoinvent version 3.

One final important note: we showed earlier that the mean of a lognormal distribution (not of the underlying normal distribution, but of the actually lognormally distributed values) is a function of both μ and σ. This means that while the application of the pedigree matrix doesn't shift the median, it does increase the average value.

| [3] | Limpert, E., Stahel, W. A., & Abbt, M. (2001). Log-normal distributions across the sciences: Keys and clues. BIOSCIENCE, 51(5), 341--352. http://stat.ethz.ch/~stahel/lognormal/bioscience.pdf. |

| [4] | Weidema, B., Bauer, C., Hischier, R., Mutel, C., Nemecek, T., Vadenbo, C., Wernet, G. (2011) Overview and methodology: Data quality guidelines for the ecoinvent database version 3 (final). ecoinvent Centre, St. Gallen, Switzerland. https://www.ecoinvent.org/files/dataqualityguideline_ecoinvent_3_20130506.pdf. |

Version history

- 2013-01-14: Initial version

- 2018-02-23: Fixed some typos, updated data quality guidelines reference, added table for ecoinvent 3.4, added Python code, added discussion of three-parameter lognormal.

Note that the entire version history of this blog is also available on Bitbucket.