A prickly subject in LCA

Technosphere matrix with processes and products

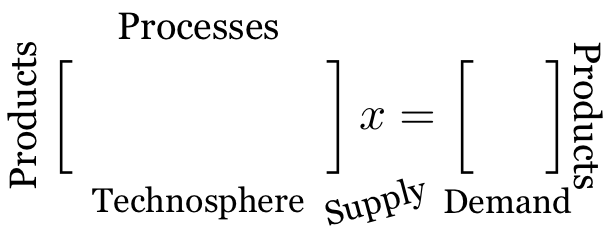

Before reading this post, please make sure you have read What happens with a non-unitary production amount in LCA?. You should already know that in the technosphere matrix, columns are processes (activities), and rows are products. The demand array (functional unit) is expressed in units of products, and the supply array is in processes:

The problem with multiple outputs

There isn't a problem, per se, with processes that produce multiple outputs. The difficulty that we in the LCA community have comes from the way we impose our model, with its rules and assumptions, on the real world. We want to classify and split the world into a series of technological processes, each with a set of distinct inputs and outputs, and then be able to solve our mathematical model for any arbitrary demand. The disconnect between discrete models and semi-continuous conditions in the real world is a classic theme in model building, and is also a challenge in designing LCIA methods and models.

The basic problem is that we have some processes, such as a combined heat and power (CHP) plant, that by their very nature produce multiple outputs, but our model allows us to specify a demand vector which includes only one output (say electricity) while requiring zero units of the other output (heat) to be produced. This is impossible, both in a real and mathematical sense.

The math of multiple outputs

Taking CHP as an example, we can demand electricity but not heat. In this system, we try to find the amount of the process "CHP plant" needed to meet our example demand. We have two equations with one variable:

In this example, the amount of heat and electricity doesn't matter, so we make our plant produce them both equally:

We could also write this in matrix form (matrices are basically just shorthand for systems of linear equations):

Obviously, the variable CHP can't be both zero and one, and so this system has no solution. In fact, any system such as this one where are more equations than variables is called overdetermined (see also Wikipedia system of linear equations). Depending on the demand vector, overdetermined systems can have solutions; approximate solutions can also be found, e.g. Marvuglia et al 2010. However, for a full-rank (i.e. each row is independent of the other rows) overdetermined system there is no general solution.

We can think of multioutput processes in different ways, depending on our background. Mathematically, multioutput processes cause an overdetermined technosphere matrix which has no general solution. Physically, multioutput processes create extra products which we requested not to be produced in our functional unit. From the "social science" perspective, multioutput processes expose a disconnect between our model assumptions and the real world.

Solutions to multiple outputs

Allocation

Allocation means splitting multioutput processes into single output unit processes (aka SOUPs) using physical, economic, or other criteria. Allocation has been and is the subject of much debate in the LCA literature, but isn't discussed further here.

Include all outputs in the demand (functional unit)

The easiest solution is to hit yourself on the head, and say that of course you simply can't get electricity without electricity from a CHP plant, or leather without beef, or kids without having your laptop peed on somehow (at least in my experience). Instead, you include all the products in the correct respective quantities in the demand vector itself. In our example system, assuming our plant produces a units of electricity for b units of heat, we would have the following system:

Including all outputs means we keep the ratio between a and b correct in our functional unit:

We can then easily solve this system:

Mathematically, this approach makes some rows in the matrix dependent on other rows - they are duplicates, just multiplied by some constant factor. Our system therefore no longer has full rank, and as such the system is longer overdetermined. There is actually only one equation and one variable.

Including all outputs is certainly the most representative of the real world, but is difficult to do when the multioutput processes are in the background system, or when there are many multioutput processes. You have to get the stoichiometry of the demand array correct to get a solution, but if your multioutput process is a few levels deep in your supply chain, you would need to calculate how much of that process is needed, and then adjust your demand array for the necessary additional products.

Substitution

If we really want to insist that we have one unit of electricity but no heat, then we can solve our system by getting zero net heat production. The first way to achieve this is substitution - we cancel out heat production by inducing a negative supply of another process that produces heat. In our example, the CHP heat could substitute for heat from natural gas combustion, which we can write as:

With the following solution:

We have solved our problem with the overdetermined system by adding another variable, so we have two equations and two variables. Our technosphere matrix is now square and of full rank. This is quite a flexible approach - the substituted process could also by multioutput, and have its other output substituted by a third process!

There are a few things to bear in mind about substitution. First, the substituted process must produce the substituted product, i.e. it is a positive number in the technosphere matrix, not an input (which would be negative). If the product is an input, then this is waste treatment, not substitution, and is covered in the next section.

Second, substitution is not defined as part of the original dataset, but rather, substitution happens automatically as long as both processes produce precisely the same product (same row in the technosphere matrix). It can be difficult to determine what is substituted, and by which processes, by looking at raw process datasets.

Third, there can only be one substituting process. If there were two, then we wouldn't know the correct balance between the two substituting processes. In our example, if there was also an old-fired boiler producing heat, then there isn't precisely one solution for the supply vector - instead, there are now an infinite number of solutions!

Now $gas = -0.5$ and $oil = -0.5$ is a solution, but so is $gas = -1$ and $oil = 0$. This is called an underdetermined system, because we have more variables than equations. Underdetermined systems are good for optimization, but not great for LCA, as we need a single supply array to calculate the life cycle inventory.

Waste treatment

We earlier distinguished waste treatment from substitution by saying that substitution processes also produce the "extra" product, while waste treatment processes consume the extra process, i.e. substitution processes will have positive values for the product row in the technosphere matrix while waste treatment processes will have negative numbers. Mathematically, there is no distinction, as our algorithm is perfectly happy to produce a solution vector with positive or negative values.

We can distinguish between two different kinds of waste treatment.

Final disposal

The first kind of waste treatment is simple. I use the term "final disposal", though other terms are used in the literature. The idea of final disposal is that the "extra" product is consumed, and no new product is produced. The most common example of final disposal is a landfill.

We can now easily solve this system for one unit of "toy":

Productive treatment

Productive treatment, such as recycling or reprocessing, takes a product which no other processes can use as in input, and transforms that product into another product which can be used. In our silly birthday party example, the packaging could be turned into cardboard:

Productive treatment has one drawback - it doesn't solve the multioutput problem. There are still two products in our expanded system, though they are now toys and cardboard instead of toys and packaging. We still need to apply one of the above techniques to get ride of our "extra" product.

Multioutput processes in Brightway2

The Brightway2 LCA framework allows for multioutput processes without allocation. Substitution and waste treatment are supported by default. The LeastSquaresLCA class (bw2calc.least_squares.LeastSquaresLCA) can also give approximate answers for overdetermined systems.